Graduate Fellowships

Couple Affected by Breast Cancer Invests in Early Detection Research

Rosemary J. Herron and her husband, Donald A. Herron (MS ’73), support a graduate student who is applying techniques from geochemistry to an urgent biomedical challenge.

Imagine a future in which breast cancer is detected through a blood or urine sample before physical signs of the disease have emerged. If that vision one day becomes reality, it may be due in part to the curiosity and generosity of Rosemary and Donald Herron.

In fall 2024, Rosemary read an article in Caltech magazine about how researchers at the Institute use mass spectrometers to measure the ratio of isotopes—atoms of the same element that differ in their mass—within minerals, molecules, and other natural materials, providing insights into their histories. One of the researchers featured in the story was John Eiler, the Robert P. Sharp Professor of Geology and Geochemistry and Ted and Ginger Jenkins Leadership Chair in the Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences.

For decades, Eiler has applied stable isotope geochemistry to fundamental questions in earth and planetary sciences, using these techniques to investigate topics such as the body temperatures of dinosaurs, the origins of organic molecules in space, and the evolution of planetary atmospheres. In the magazine piece, Eiler said that the Orbitrap mass spectrometer, which he developed and refined with Thermo Fisher Scientific, had become sensitive enough to unlock vast amounts of information about metabolism and disease in the human body.

Soon after the article was published, the Herrons had lunch with Eiler. Rosemary asked about the Orbitrap’s medical applications. When Eiler mentioned a project in his lab focused on searching for the isotopic "fingerprints" of breast cancer, Rosemary and Don were immediately intrigued.

The Nurse Who Became a "Forever Patient"

The Herrons met in Providence, Rhode Island, when Don was an undergraduate at Brown University and Rosemary was in nursing school. Don went on to earn a master’s degree in geology at Caltech in 1973. The couple settled in the Houston area, where he worked in the oil and gas industry as a seismic interpreter and geophysical consultant and she was a nurse.

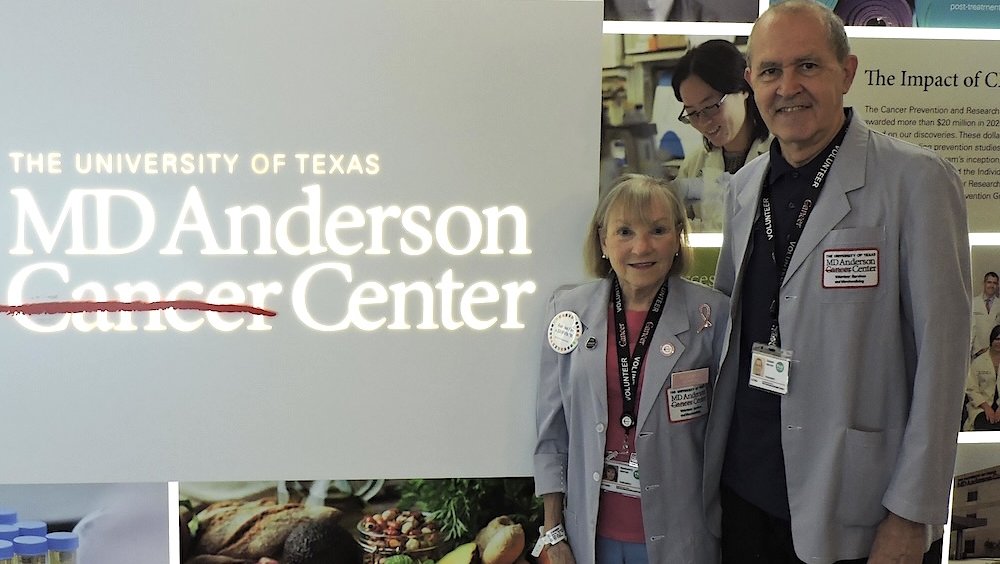

In 2001, Rosemary was diagnosed with breast cancer. Treatment pushed the disease into remission, but it returned in 2012. Considered a "forever patient," she receives treatment at the MD Anderson Cancer Center every three weeks. The Herrons also volunteer at the center. Don helps patients find their way to their appointments, and Rosemary speaks with them, answers their questions, and—as a living, breathing example of resilience—gives them hope.

During their lunch with Eiler, the couple sensed another opportunity to help breast cancer patients. They decided to provide three years of fellowship support for Simon Andren, a graduate student in geochemistry who is working on the early detection project.

A Lab of Open Minds and Bold Ideas

Andren arrived at Caltech with a bachelor’s degree in earth science and data science. As an applicant to the geochemistry program, he had no expectation of working on a biomedical project, but he did have an open mind. And in joining Eiler’s lab, he entered an environment where isotopic structures of molecules and minerals are used to pursue a wide-ranging—and ambitious—set of goals. The idea of bringing his data science and computational skills to bear on a challenge like cancer was enticing.

In Andren and Eiler's project, the goals are twofold: to develop a less invasive diagnostic tool for cancer and to improve cancer treatment through a comprehensive understanding of cancer cell metabolism. The researchers’ approach involves studying the arrangement of isotopes at the atomic scale in small organic molecules central to metabolism, known as metabolites. Because cancer alters metabolic pathways, it leaves behind subtle changes in the isotopic composition of these molecules.

Early work has focused on purifying samples of breast cancer tissue and measuring the isotopic signals in the target molecules. Eventually, Andren and Eiler aim to characterize and reliably detect these isotopic fingerprints in minimally invasive blood and urine samples and interpret them in the context of metabolic reactions.

The researchers chose to focus on breast cancer partly because it’s a leading cause of death and partly due to the availability of disease specimens. But breast cancer represents only the first front in this line of research. "Once we understand how to do this—how to move through the pipeline from tissue, blood, and urine samples all the way to a scientific conclusion—we’ll be able to study the dysregulation of metabolism in many different kinds of cancer," Eiler says.

The Impact of Donor Support

Eiler and Andren say that support of graduate fellowships provides faculty and students the freedom to make decisions based on scientific factors rather than predefined funding objectives, and to focus on research rather than grant applications.

"It feels really wonderful to have people believe in you," adds Andren, whose graduate fellowship is also supported by Caltech Trustee Charles Trimble (BS ’63, MS ’64) and his wife, Liying Huang. "Their belief encourages me to keep working hard throughout the inevitable setbacks in the lab and builds my confidence that this project will lead to real progress and end in meaningful discoveries."

The Herrons began supporting Caltech more than 40 years ago through contributions to the annual fund. In 2022, they made a gift to establish and endow the John R. Herron Lectureship, named after Don’s father. Through the lectureship, Caltech hosts scholars recognized for their broad societal impact in the applied earth and planetary sciences and related engineering fields.

The couple says their approach to philanthropy is simple. "We want to make life better for those who come after us. At Caltech, the opportunities to do that seem to be limitless," Rosemary says. She notes that one does not need millions or billions of dollars to make a difference.

Ever the geologist, Don adds, "You don't need to turn over too many rocks to see places where you can do some good with the resources that you have."